If not “secure/open” assessment, what will we do about the GenAI assessment crisis? In this article, I propose a purpose-led revision of assessment standards.

This is an approach I’ve written about before, drawing on musings by Phillip Dawson earlier this year. Dawson suggested there is a need to reconsider the standards for success we use in our assessments, in light of students’ use of generative AI. I agree that we need to do this, though I disagree that it’s because of GenAI.

The way we assess student work is by defining the standard of quality we expect from that work, then comparing the work to our defined standards. But we are often quite terrible at defining meaningful standards.

Let’s take marking rubrics as a case study in designing HE assessment standards.

The trouble with rubrics

I’ve mostly worked in parts of HE that use an analytic rubric to assess the quality of student work. (There are two other key types of rubric — holistic and developmental.)

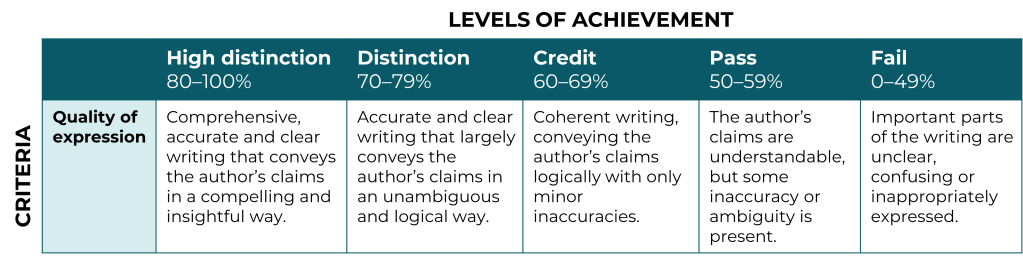

An analytic rubric looks a bit like the below.

The key features are a list of criteria (the vertical header) described at various levels of achievement (the horizontal header, here broken into five grade bands with associated numeric scores).

The trouble? Rubrics with criteria and levels of achievement are both too prescriptive and far more subjective than they purport to be. On the one hand, the criteria being assessed are limited and constrained; on the other, the descriptors at each level are blurry and loose.

In the example above (designed by me as a prototypical example, not a very bad or very good one), what constitutes an “insightful way”? What differentiates “minor” inaccuracies from “some” inaccuracies? If the student’s writing is “confusing” to the assessor, is that a quality of the writing or of the reader? And do these descriptors identify everything that an assessor might value in a student’s quality of expression?

There are important reasons why we use analytic rubrics, of course. If we didn’t define rubric criteria, we (students and teachers) would struggle to share an understanding of what matters about a task. If we didn’t describe what achievement looked like, we wouldn’t have benchmarks to aim for. These are undeniably helpful for shared understanding.

But when assessment designers have to describe five distinct levels of achievement for each criterion, the descriptions start to blend into one another. Often, the descriptor for a high distinction sounds essentially the same as the description for a distinction. In more than one case, I’ve seen level descriptors that ask for less than those at a lower grade band.

We have become locked into a very specific pattern of assessing student work.

First we set criteria which are arbitrary in the first place (a friend pointed out to me that “correctly applies referencing style” is the highest-weighted assessment criterion across many students’ entire degrees). Then we come up with standards (levels) of achievement that are not even relevant to the purpose of the assessment. What does “distinction” even mean to a student in the first semester of their course? And why should that result be carried forward with them as part of their weighted average for the entire degree?

So what can we do differently?

Returning to purpose

Firstly, we need to recalibrate the purpose of each assessment. When is an assessment for…

- helping teachers understand what students need?

- helping students see their own progress?

- discovering and supporting a student’s style?

- determining which students should be given an award or additional resources?

- ensuring students can competently, consistently perform to a minimum standard?

Identifying the purpose of the assessment will help us identify what kind of response is needed — a quantitative grade, a confirmation of competency, a descriptive evaluation of what the student has produced, a message to the student about how to improve.

Redefining assessing standards

Then, we need to reconsider what our standards are for assessing student work. If not a gradient of achievement (i.e. an analytic rubric like the one above), should the assessment be…

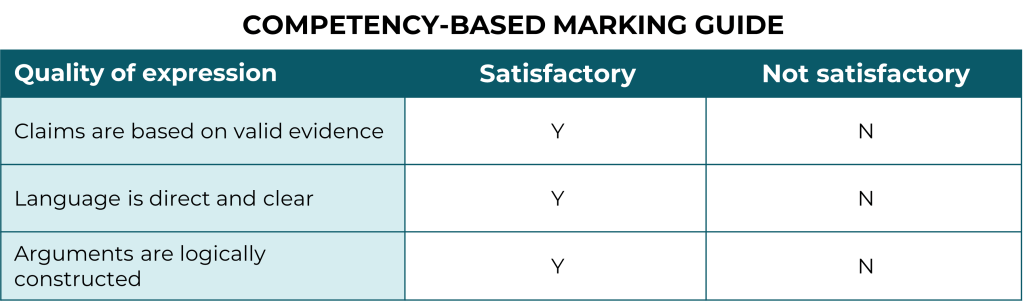

Competency-based assessment

In a competency-based assessment, the student either can or can’t meet the core requirements of the task. This is appropriate if the entire purpose of the assessment is to determine whether credit should be awarded, or whether the student should be permitted to perform the task without supervision thereafter.

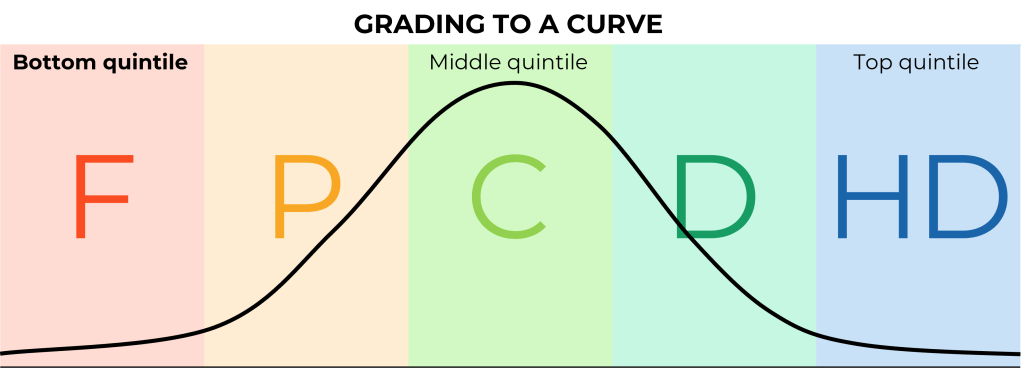

Norm-ranked assessment

If the standard of quality is not absolute, but is about determining which students are doing better than which other students, norm ranking is necessary. This is where each student’s performance is rated against all other students’ performance. This is relevant in selection processes, say when all the students are competent, but you can only promote a fraction of them.

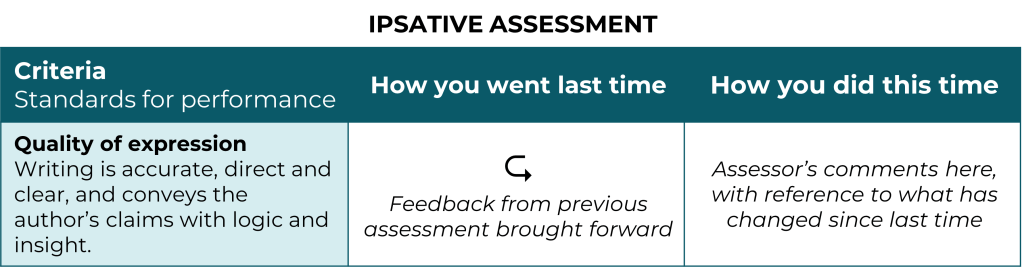

Ipsative assessment

In ipsative assessment, each student’s performance is compared to their own previous performance. The focus is not on absolute capability, but on progression. This, arguably, is the only kind of standard that actually measures learning (that is, it involves observing positive change).

Narrative assessment (ungrading)

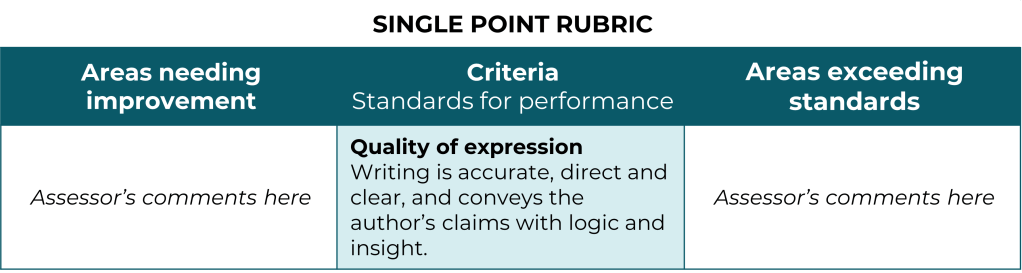

Or perhaps the assessment is aimed at qualitatively describing rather than grading the student’s work. The “rubric” shown below is called a single-point rubric, but some argue that it’s not a rubric at all, because it doesn’t involve scoring. Instead, it identifies criteria (the attributes of performance that matter to the assessor) and requires the assessor to describe the student’s effort towards each. It’s certainly not the only way to produce a narrative assessment, but it’s one structure that is gaining in popularity.

Depending on the standards we define, we can develop appropriate rubrics, answer guides, marking checklists or whatever else we use to structure our judgements of student work.

These tools serve many audiences, including assessors making judgements, students making sense of what’s being asked of them, and quality auditors assuring the educational alignment of the course.

Grading and gameability

While transparent assessment standards are incredibly helpful for setting a shared understanding of what the task is, they are also what makes assessments gameable.

By this, I mean: as soon as we define a winning condition, we enable an assessment task to be played like a game. Any task that involves assigning a quantitative value, even if that value is 0/1 (fail/pass), can be gamed. Assigning value like this requires rules, and rules invite gamesmanship.

For example, if a task is graded via a rubric, we have to match the student’s work to specific descriptors on the rubric. If a student wanted to game this using GenAI, they might feed the rubric descriptors into an LLM. They could also pass them to a contract cheating vendor. Or, following the maxim “Ps get degrees”, a student can simply aim at the lowest-level descriptors to exert the minimum effort required to pass the assessment. And the requirements for a “pass” mark are often well below a standard we might actually consider passable.

So we need to be very aware of what kinds of games we make possible to play — and when and why we would consider such games “cheating”.

If students should be able to perform a task to a very specific level of precision (say, applying a mathematical equation or performing heart surgery), then a rubric-based assessment strategy is not appropriate. “Ps get degrees” should not apply here. I would argue that a medical student who “completes operation with minor inaccuracies” is not ready to practice surgery in the world.

Banning generative AI is also inappropriate in this case, because such tasks should be provided optimal conditions for perfect completion, not artificial barriers. Isn’t the point that the task is done correctly and safely? If the task is best done correctly and safely with particular digital (or other) tools, then the presence of those tools should validate, not invalidate, the assessment evidence.

Conversely, it may not be appropriate to use grading at all. If an assessment is for the purpose of diagnosis (the teacher identifying the student’s needs or work style), then a descriptive approach involving analysis and feedback may be the way to go.

It’s pretty difficult to “game” an assessment that has no winning conditions. All a student has to do is submit something. If it’s something pointless, then the feedback they receive will also be pointless, and they have wasted the opportunity to learn from it.

Obviously, there are times when we do need to produce a quantitative judgement. Most importantly, we need to know when:

- a student is not ready to progress to further learning

- a student is ready to practice a real skill with real risks in the real world.

To my mind, these are the two reasons why we would need to judge student work in a quantitative way. So, in the next proposal, I offer a way of thinking differently about teacher judgements of readiness for progression.

REFERENCES

- Blum, S. (2020). Ungrading: Why Rating Students Undermines Learning (and What to do Instead). West Virginia University Press. https://doi.org/10.31468/dwr.881

- Dawson, P. (2025, February). Grade inflation, marking to a curve, or standards creep [Post]. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7300303779692756992/

- McTighe, J., Brookhart, S. M., & Guskey, T. R. (2024). The Value of Descriptive, Multi-Level Rubrics. ASCD. https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/the-value-of-descriptive-multi-level-rubrics

- Reynoldson, M. (2025, July). Where to from here? Foster educational relationships. The Mind File. https://miriamreynoldson.com/2025/07/01/where-to-from-here-relationships/

- Reynoldson, M. (2025, March). Soaring standards in the age of AI assessment.The Mind File. https://themindfile.substack.com/p/soaring-standards-in-the-age-of-ai

Leave a reply to Ben Lawless Cancel reply