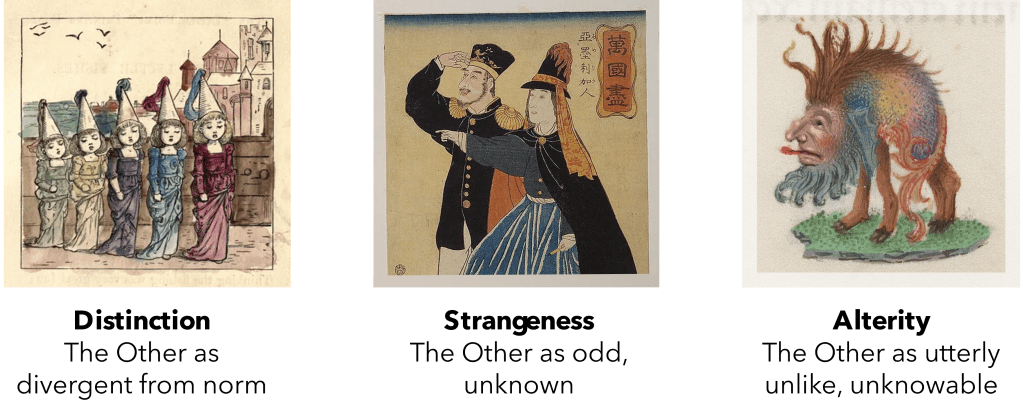

According to Emmanuel Levinas, there are three ways to be different.

Difference as distinction

One is to be distinct: distinguishable from the rest. There’s something about you that makes you stand out – perhaps hair of a different colour, or claiming to like pineapple on pizza. Differences of distinction help us distinguish between multiple examples of things within the same category, like various styles of upholstery on sofas in a shop.

When our differences are distinctions, we ultimately see ourselves as parts of a unity, parts that fit together and perhaps even need one another, like yin and yang.

Difference as strangeness

The second is to be strange. To be different in a way that people don’t understand, and that very likely makes them feel uncomfortable – like migrants with not much English and mysterious cultural customs, or people with neurodivergent traits whose behaviours we don’t understand.

When our differences make us strange to one another, we might feel discomfort, or even consider each other exotic, mysterious, exciting. But even strange things can be made mundane through engagement, through learning and familiarity.

Difference as alterity

The third, and the one Levinas wrote reams about, is alterity. He used the term not simply to mean alternate, but to describe a state of absolute Otherness. Alterity isn’t just about being distinctly different, or unknown, but about being fundamentally unlike, being unknowable. What is most difficult about this concept of alterity is that by its nature, we can’t completely reach a clear definition of it, because it is not like anything we know. If we came to know it, it wouldn’t be alterity.

I’ve written before about feeling like I was different. And truthfully, in many more ways than not, I differ because I suspect I am strange. My wife has always told me she saw herself as an alien around other “normal” people, and an adult diagnosis of autism has helped equip her with some kind of framework for that. I don’t have a diagnosis, but I don’t need one to know that I feel less alien around other aliens.

The challenge Levinas pressed on us, though, was not a command to know the Other better, or to try to find some likeness, some kinship with those who are different from us. Rather, he argued, we have a fundamental ethical responsibility to the Other.

The relation with the other [is] an ethical relation; but inasmuch as it is welcomed this conversation is a teaching… Teaching is not reducible to maieutics [that means questioning to draw out correct answers]; it comes from the exterior and brings me more than I contain.

Levinas in Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority

Or – I have a responsibility to that which I cannot fully understand; and I am responsible because I cannot fully understand it. The Other holds meaning that surpasses my own ability to comprehend – something I can and must respect, because I cannot replace it.

Can we care for someone we cannot understand?

It seems that an awareness of the Other is at the heart of an ethics of care. Four elements central to an ethics of care are:

- Relationships between people, which are always the contexts in which ethical choices are made. Whether parent and child, seller and customer, teacher and student, or doctor and patient, we extend care to those others who matter in our worlds.

- Responsibility towards each other, which people in relationships must take up in order for care to arise. As Levinas suggests, we have a fundamental responsibility to that which is other to us.

- Emotions, which emerge through all relationships and so shape the nature of those relations – the affective flows between ourselves and others.

- Actions, which are the essential manifestation of ethical decisions, and which happen in real time and real contexts of worldly entanglement. That is: ethics is only ethics if it is instantiated through action, not merely through abstract hypotheticals.

But it is obvious that in the face of the Other, each of these elements confound. It is difficult to grasp the nature of a relationship with someone we do not know, and it seems counterintuitive to accept responsibility for them. Even harder is the problem of emotion. When there is something we find strange, something we don’t know or understand, discomfort is natural. Fear, frustration, disgust. Strangeness is, all too often, a problem. And when the Other is not merely unknown, but unknowable – as in alterity – then the only escape from strangeness is escape from the Other.

While it is easy, natural, to care for and love those who are like us (those who belong to the same group, but with some variation – our sisters, our countrymen) it is work to extend care to those who are unknowably unlike us. And worst of all, it’s the kind of work that pays absolute peanuts: hospitality.

Much has been made of Jacques Derrida’s writing on hospitality. Derrida distinguished between conditional and unconditional hospitality, where conditional hospitality is a reciprocal exchange of welcome and visitation between host and invited guest (agreed, codified, arranged). We can offer conditional hospitality when we know our guest, and when we have agreed on the terms of the visit. Distinct or strange they may be, but our guest can at least assure us of reciprocity.

But unconditional hospitality is not, or cannot be expected to be, reciprocal. Unconditional hospitality is a radical generosity – a welcome as a gift, rather than as one end of a trade. When alterity is our guest, hospitality can only be unconditional. The labour of caring for the Other is unpaid.

Is this something we are capable of extending to those we do not, and cannot, understand? Are we actually able to choose care for those utterly unlike us?

Leave a comment