If not “secure/open” assessment, what will we do about the GenAI assessment crisis? In this article, I propose we invest in genuine, long-term relationships between students and teachers.

Education is not a process, a product, or a service. It involves all three of these, but is more than all of them combined. Education is a relationship between a student and an educational entity. Of course, that doesn’t only implicate teachers — students also relate with each other, with enrolment and support staff, librarians, counsellors, coordinators and many other members of the educational community.

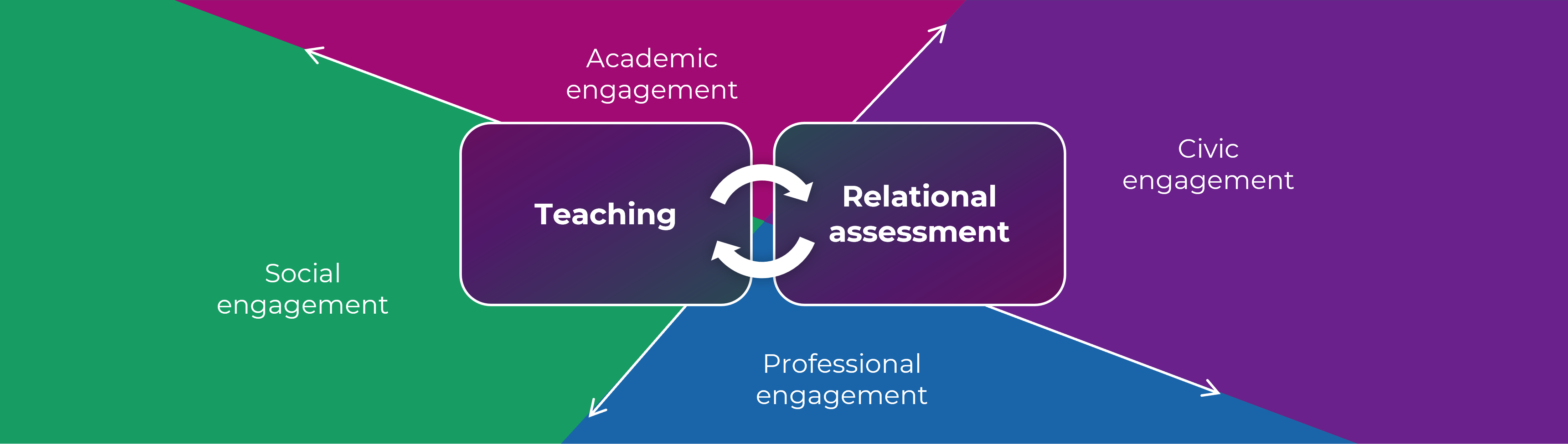

It is the teacher-student relationship that is central to effective assessment: students do assignments; teachers do assessments. Teachers assess students’ work in order to find out how their students are making sense of their worlds.

In order to produce informed, holistic assessments of a student’s capabilities (that is, what they can do over time, under a range of conditions), those capabilities need to be observed over time, under a range of conditions. This isn’t new information.

But if our assessments of student effort are to be more than snapshots of output or work in progress (which in themselves tell us little about how students are making sense of their capabilities), our assessments must involve seeking evidence of their engagement not only with academic ideas, but of social, civic and professional ones, to construct an understanding of their worlds.

If we’re going to try to do that, we need to know our students. We need to know them over time, under a range of conditions.

We need to build conditions in which teachers can work with students over extended periods of time — ideally for the whole of their degrees. Of course this will always be imperfect. Students change their study plans mid-degree. Teachers resign, go on leave, or don’t teach all the subjects the student is doing. But if our higher education environment is not configured to foster any enduring educational relationships, then we’re trying to educate in artificial conditions.

Some ways we might do this:

Mentoring and supervision

We might connect each student with one or more mentors to support them throughout their degree. This approach is offered by Adrian Jackson of Pilgrim Theological College, University of Divinity. Inspired by formation panels for Uniting Church ministry candidates, Jackson proposes a mentoring group that might include academic supervisors, student peers, or professional staff. He invites university leaders to “make learning a conversation between people about skills, character and growth”.

Mentors would need to have sufficient depth of knowledge of the student’s course to support the student through multiple assessments across multiple units over time; and if there are multiple mentors for a student, they need to communicate with one another in order to support the student’s progression in an informed and relational way.

Ungrading

Significant critique has been levelled at the widespread (but surprisingly new, at less than 200 years old) practice of grading student work. These critiques sound most vehemently in creative arts and humanities subjects, and when assessment is for the purpose of development. Susan Blum’s marvellous Ungrading is often regarded as the rallying cry for the ungrading movement.

As well, Jason Gulya is a thoughtful and important voice on this topic, and someone who is constantly working out loud as he explores the possibilities and challenges of alternative grading.

Ultimately, the question of whether to grade is a question of whether we value students’ work quantitatively or qualitatively. Feedback (responses, descriptions, praise, critique, suggestions) is qualitative. A grade quantifies these responses by presenting them as measurements on a scale (whether that scale is pass/fail, levels of achievement or an alphabet sequence of letter grades).

Quantitative thinking is useful, especially at scale, but it risks essentialising student performance (“he’s a C student”) and shifting motivation from the ideas to the score. By eliminating grades other than judgements of readiness to progress, we restore our students’ focus on making meaning rather than manipulating numbers.

Narrative assessment

Instead of providing discrete grades and feedback for each assessment task, we might ask both assessors and students to engage in narrative assessment: qualitative evaluations of the work, which are added to an ongoing narrative account of the student’s progress. This helps capture an ongoing story of the student’s learning through the degree from multiple perspectives, including the student’s own.

A narrative evaluation model is successfully practiced at Evergreen State College in Washington, though of course there are many other ways it might be implemented.

Industrial relations hygiene

These actions are seemingly simple, but they may be the costliest element of any strategy for protecting assessment integrity. Higher education institutions must:

Improve teacher-student ratios, to ensure adequate time and opportunities for connection between members of the educational relationship.

Pay teachers appropriately for assessment feedback time (“marking”). In current sessional academic contracts, marking time is paid at a lower rate than all other academic teaching activities. Given we know that feedback is one of the most important influences on learning, for good and for ill, this is deeply unjust and likely has far-reaching educational consequences.

Issue long-term teaching contracts, to increase the chances of the same teacher having oversight of a student’s work over many units or full degree.

Reduce sessional precarity, in support of the same goal as well as teacher wellbeing and retention.

Abolish marking-only contracts, to eliminate the chances that any assessment is marked by a person who has not helped the student learn.

These are all troubling and long-standing educational issues, each of which drags at the quality of the total experience for all those involved in educational relationships, eroding trust and mutual understanding, and making near-impossible the kind of intellectual hospitality that is at the core of good educational relationships.

They are often issues perpetuated out of financial necessity. But personally, I believe that if we can’t address them, it doesn’t much matter what else we do.

This proposal, of course, is focused on all of the inner workings of a student’s educational journey. It’s not about confirming their competence, but about travelling alongside them and growing an understanding of their growing understanding. For the kinds of courses where “competence” is not relevant (where every pathway is unique, where grammars are plural and emergent, where the aim is art rather than technique), this kind of assessment is perfect.

But for those kinds of course that license someone to practice in specific and measurably correct ways (medicine, pilot training, engineering), we need clear and unambiguous assessment for qualification. This is the focus of my final proposal.

REFERENCES

- Biesta, G. (2021). World-Centred Education: A View for the Present. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003098331

- Blum, S. (2020). Ungrading: Why Rating Students Undermines Learning (and What to do Instead). West Virginia University Press. https://doi.org/10.31468/dwr.881

- Evergreen State College (n.d.). Narrative evaluations. Evergreen State College. https://www.evergreen.edu/our-learning-approach/narrative-evaluations

- Harvey, M. (2017). Quality learning and teaching with sessional staff: systematising good practice for academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 22(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2017.1266753

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

- Pilgrim Theological College. (n.d.) Ministry Formation at Pilgrim. Pilgrim Theological College, University of Divinity. https://pilgrim.edu.au/formation/

- Sellar, S. (2012). ‘It’s all about relationships’: Hesitation, friendship and pedagogical assemblage. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 33(1), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2012.632165

- Reynoldson, M. (2025, July). Where to from here? Decouple learning from qualifications. The Mind File. https://miriamreynoldson.com/2025/07/01/where-to-from-here-decouple-assessment/

- Reynoldson, M. (2025, June). Assessment is what the teacher does.The Mind File. https://miriamreynoldson.com/2025/06/03/assessment-is-what-the-teacher-does/

Leave a comment