In the mad scramble to lock down assessment security and devalue the role of developmental assessment, have we lost the ability to trust students altogether?

Assessing university student work in the current context is absolutely fraught. I should know: it’s a marking week again. 62% of my students have acknowledged AI use in their papers. And believe me, not everyone who’s used it has acknowledged it. Students everywhere have access to a passel of GenAI tools, both free and institutionally-provided. Who’s to say their work isn’t AI-generated? We just can’t be sure. Unless…

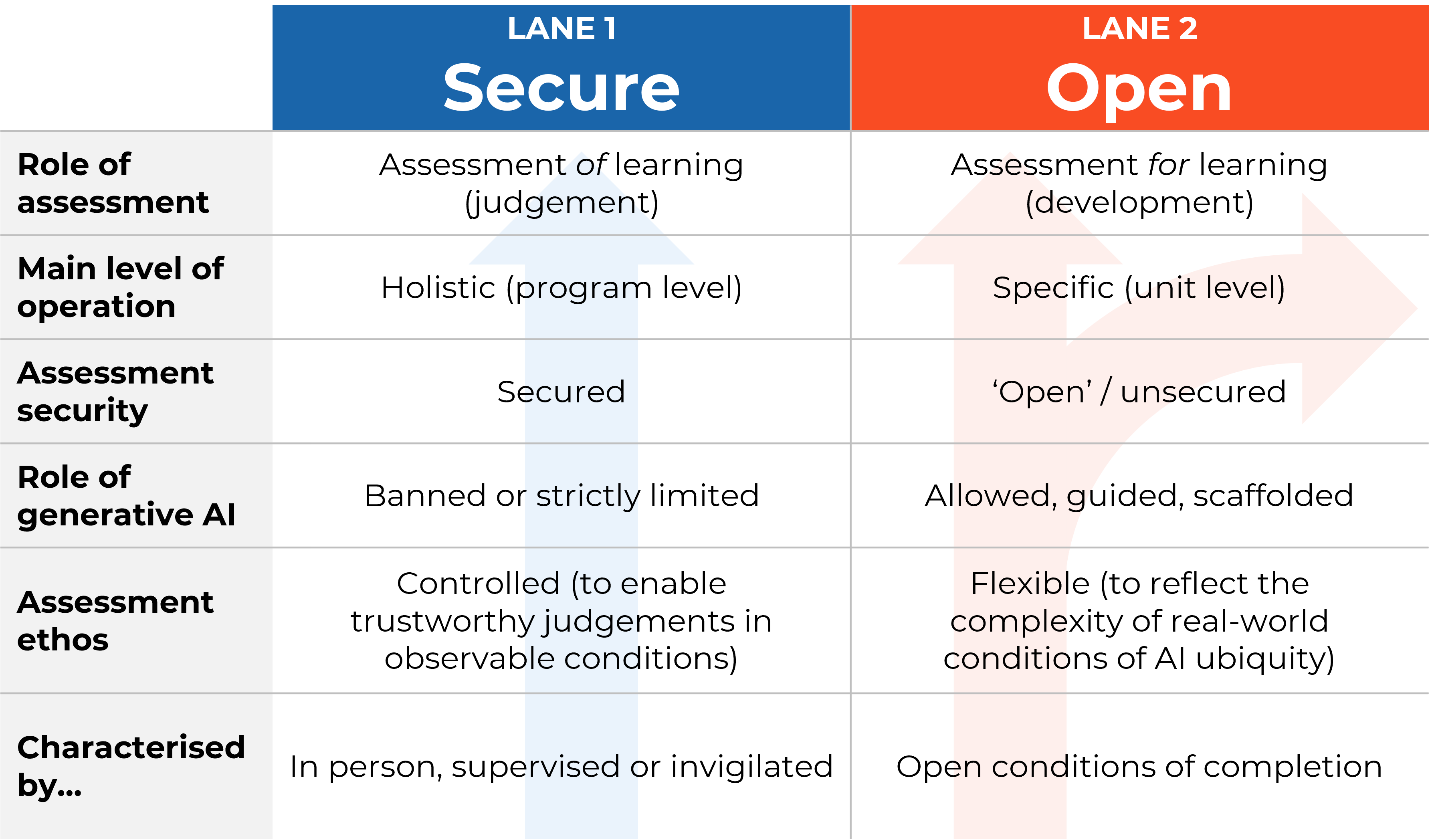

Danny Liu and Adam Bridgeman of the University of Sydney proposed a “two-lane approach” to enable educators to assign and conduct AI-conscious assessments in their courses with confidence.

If categorised according to the two-lane approach, assessment is either:

The two-lane approach offers a simple solution to the problem of assessment security in a context where AI has busted all the locks. I have critiques of it based on my values and ethics, but here I will focus only on why, in my opinion, it doesn’t actually work.

It doesn’t work for three big reasons.

1. It’s a “simple” solution to a complex, continuously-evolving, ill-defined problem.

If it’s a solution that appears a little too clean, that’s because it’s a discrete response to a fluid situation. Its creators know this. They have written so many caveats and implementation conditions into their FAQs because they know it’s never really one-or-the-other.

The real issue isn’t that it is a binary model (its creators would tell you it’s much more nuanced than that), but that by calling it a “two-lane” approach, they’ve packaged it as a binary model. This means it will be implemented like one. It appears as if the thinking has been done for us, so we won’t do any. We’ll choose a lane and drive in it — or we’ll decide they don’t fit and take a slip road. Like Guy Curtis at UWA.

Curtis argues that a “middle lane” is required, because the two-lane approach will lead to poor teaching practice. He characterises the model as “all or nothing” AI use, which isn’t accurate: it’s more correctly described as “secure or open”, although I argue this is a false dichotomy too. Let’s unpack this.

2. It implies that it’s possible to secure assessment conditions against AI use.

How idealistic! Lane 1 relies on the premise that “secure” is even a genuine option.

First, an admission. I’m a person who has deliberately avoided working with programs involving exams and proctoring. I know a lot of stuff, but when it comes to invigilated assessment, I do not know my stuff. So I’ll avoid any description or critique of existing assessment security measures.

But do we really believe that, as the applications of Generative AI continue to expand, they won’t extend to more ways of circumventing our current and future security measures?

Say in 2025 we make students enter an in-person examination room, have their fingerprints scanned to verify identity, then give them a pen and a paper to write their essay, while they are surveilled by both a video camera and a human supervisor.

What if, in 2026, some developer embeds a GenAI app into a wearable device that enables those students to prompt using motion gestures, then write out the resulting output by dictation?

Security from AI technologies is a slippery goal, and we will always, always be fumbling.

So “secure vs. open” isn’t a meaningful distinction either.

Perhaps we could say an assessment is “more secure” or “less secure”. Yes, layers of supervision and controlled conditions would increase that security. But it’s simply not honest to claim that in person assessment methods are/always will be fully secure.

Furthermore, “open” assessments aren’t unsecured. We still care whether or not it was the student’s own work. We still use checks and balances for this, to the best of our ability. That’s not pointless, even if it’s not bulletproof. We do the best we can.

3. Lane 2 is a rug-sweep.

It’s a way of acknowledging (or maybe guaranteeing) that students are going to use AI, no matter what. Your Lane 2 assessments are open, enabling students to complete tasks flexibly using the tools available. The guidance material suggests that AI use should be scaffolded and supported, not simply a free-for-all, so that by undertaking these assessments, students develop AI skills (I refuse to say AI literacy, so there).

But, of course, Lane 2 is non-invigilated. Which means no matter what we teach them, we can’t know for sure what they’re really doing. So while this lane is supposed to be developmental (assessment for learning, but Tim Fawns doesn’t like that term, or formative, but Danny Liu doesn’t like that term), we don’t really know how they’re developing.

My view is that, in a two-lane approach, the assessments in this lane are going to count for nothing. Liu and Bridgeman argue that they should still be graded, but this reads like apologetics to me. If they’re having to argue for still grading them, it’s clear that they are already perceived as inconsequential.

It also bothers me profoundly that they have suggested Lane 2 assessments should be pass/fail only (rather than using levels of achievement). It seems obvious that these are the tasks for which differentiated feedback is most needed. These are the ones where how students choose to do the task matters.

It’s clear that Lane 1 assessments are the ones intended to earn students their degrees. Lane 2 is nuanced, complex, problematic, messy, unreliable. In other words, it’s where the learning happens. And, as we’ve seen in the scramble to protect and secure and control assessment in the age of AI, it is now worthless as evidence, leaving us with nothing but a decaying legacy of high-stakes invigilated assessment.

This lane resolves nothing. It just puts all the stuff we’re worried about into a neat stack.

So what are we supposed to do?

I’m not claiming to have a better solution than the two-lane approach. Liu and Bridgeman are formidable, constructively critical minds in the higher education assessment and technology space. I’m no match and I know it.

Ok, I do have a solution, but that solution requires a radical dismantling of the entire assessment system, which has been fundamentally flawed since long before LLMs became a consumer product.

Higher education assessment currently isn’t valid.

It just isn’t.

We assign staged and artificial tasks under staged and artificial conditions, then assess students’ attempts by scoring them according either to our own opinions, or to a standardised veneer of objectivity (rubrics).

Lane 1 certainly isn’t valid: it’s controlled, isolated and divorced from reality. It also embraces the worst aspects of assessment, the ones that equity and inclusion advocates have spent decades challenging. Many students do much worse under time-restricted exam-style conditions — myself included. I think grades are stupid, but if we’re being specific about this, exam conditions usually put me one to two grade bands below my average. I’m a very high achiever, and for me, this doesn’t make the difference between a pass and a fail. But I’m not who I’m worried about here.

But Lane 2 isn’t valid either. As Liu and Bridgeman themselves point out, if an assessment is unsecured, there is (by definition) no way to enforce the process students use to complete it. Plagiarism detection software is unreliable and poorly implemented. AI detection software is useless and actively harmful. Teacher “hunches” are biased and discriminatory. We can only do the best we can.

We need to learn to trust. Now, more than ever.

I’ve written before about trust in learning. I wrote then about the need for students to trust their educators in order to learn from them, but today I want to focus on educators trusting their students.

The whole GenAI-in-assessment conversation is one that demonstrates profound distrust in students. And it seems justified: the overwhelming majority of university students use GenAI. The overwhelming majority of ChatGPT users are students. The evidence is stacking up: the odds are, any given bit of student work will be AI-augmented. And (given that far fewer non-students are using AI) it’s not preparing them for a world that’s doing the same.

Our students are overwhelmed, cynical, financially-compromised. They see peers doing it, and that makes it feel ok. Students are tired of being treated like children. They’re smarter than we think, and they will find ways around us. They’re also not as smart as they think, and they will make so many terrible mistakes.

So how do we find a way to trust again?

I never said it was easy. Trust decays exponentially. But I believe that in order to approach this problem, we have no genuine option but to reflect on what is preventing trust between students and educators.

Let’s fight that, not each other.

The two-lane approach to assessment is not terrible. It has a huge amount of merit as a thinking tool. But it is deceptively complex (I asked Danny Liu for guidance to characterise it correctly, and I’m sure I’ve still got it wrong), yet still fails to acknowledge the myth of “assessment security” in the age of AI productisation.

It also offers a tidy-seeming — yet impossible to truly implement — governance solution that will do nothing to stem the loss of trust in education.

Leave a comment