In divided times, critical thinking is not enough. We have to play the believing game. This is an exercise I’m trying in my own speculative writing on technology futures.

It’s in our nature to doubt. When we hear a suspect claim, we tend to look for the gaps, the faults, the reasons not to accept it. We call this tendency “critical thinking”, or “discernment”, or “caution”. Peter Elbow called it “the doubting game”.

In academia, we consider doubting to be a commendable practice. An ability to critique something is a key skill of any scholar. The great scientific method itself is built on a foundation of doubting: a hypothesis is treated as false until evidence can be found to support it. Thereafter, we treat it slightly more kindly, but always with suspicion.

This is an excellent structure to follow when dealing with mechanical things. But as Elbow pointed out, doubting has real limitations and risks when it comes to matters of value. He introduced something he called “the believing game” as a rule in his writing workshops, in which everyone contributes a piece of their own writing and reads each other’s.

How to play the believing game

The idea: believe everything you read. Believe it as hard as you possibly can. Climb inside and walk around. Search for its virtues, no matter how hard they are to find.

This enables us to find strengths we otherwise might have missed. It allows us to engage with ideas that are uncomfortable, unfamiliar, perhaps incompatible with our own beliefs. We have to make a conscious effort to side with hope.

The believing game (or “methodological believing”, as Elbow sometimes called it) isn’t a replacement for the doubting game. Rather it’s a necessary complement.

For anyone who works with feedback (teachers, people leaders, Yelp reviewers… I jest) you already know how important it is to address both strengths and weaknesses in your feedback. It helps engage and support the receiver, but it also helps you, as the reviewer, to approach your review more constructively. You have to hold onto the assumption that the receiver is working in good faith. And then you have to appreciate what it is they are trying to do. Whether they’re doing it well or not, you believe they can. Otherwise, why bother giving them feedback at all?

(I write this with the assumption that nobody here would give feedback for the sole purpose of making someone feel shame.)

The believing game, therefore, is a relational practice. Unlike the procedural discernment of the natural scientist, the methodological believer is engaging with a social truth: the beliefs, ideas or values of someone who isn’t themselves.

Believing as relational critique

They say this is a “post-truth” time. I’m not going to get political here, and I’m no historian, but I’m not sure there was a “truth time” before it. Because although we all love to play that doubting game, we really aren’t very methodological about it.

We’ll doubt a claim all the more when it goes against our existing beliefs, or when we dislike the person who makes it. We’ll gather up all the shiny supporting arguments for our own beliefs. Doubting comes naturally — but deliberate, effortful critical thinking does not.

And neither does deliberate believing. Elbow was trying to train his student writers to develop their believing muscles, to be able to believe in each other’s work despite their differences or weaknesses or aesthetic preferences.

The end goal isn’t to believe every imperfect manuscript is great as it is. Rather, it’s to try as hard as we can to believe in the person who wrote it. They can make it better. They want to. In this view of feedback, there is no such thing as “don’t take it personally”. Believing is entirely personal — it’s a deliberate act of care and trust.

In a way, this idea is very like the introduction of emotional intelligence in the 1990s as a complement to cognitive or rational intelligence. While cognitive thinking and traditional critique are still essential to social inquiry, emotional awareness and creative thinking provide depth, relationality and personal access to ideas and perspectives — especially those which are different or opposite to our own.

But you don’t win the believing game by converting someone else to your own beliefs, or by abandoning your own and converting to theirs. It’s not about rhetoric or persuasion, but about searching for hope. You win by connecting with the heart of an idea, and helping it beat strong.

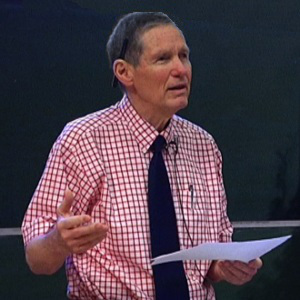

The wonderful Professor Peter Elbow died last month, aged 89. His work has influenced and inspired generations of writers and their practice. You can read his own words on the believing game here, and learn more about its origins as a writing workshop technique.

.

Leave a comment