Some notes on the presentation about university allyship given by Phillip Abramson and me at the recent Third Space Symposium 2024.

I love, love, love to think about intersections. All the ways in which our understandings of ourselves are plural and competing and overlapping and which frequently force us to decide who—and what—to be in a given moment.

This is why, when Phillip Abramson mentioned work they were doing to establish a grassroots ally network for staff at Monash University, I leapt on it and said “let’s present this!”

So we ended up on the bill for the Third Space Symposium 2024, which is really about managing work identities at the margins of academic and professional roles (learning design, educational technology, research management and leadership, academic quality… there is no limit to the types of work that can find itself here).

These kinds of “third space” roles are uncomfortable. They’re boundary crossing. They make us feel othered in both parts of the binary role architecture of the university. Which is why those who hold them already possess the empathy, the access, the positioning and the power to perform acts of allyship with others who find themselves at the margins.

What is allyship?

Phil gave the most gorgeous definition of allyship—it’s not about “being an ally”. To ally is to act: it’s a verb, not a noun.

For me, this connects in with the idea of “queer” in queer theory and activism, where the sentences should be phrased “to queer”, not “is queer”: it’s not that we are strange, but that we make strange the notion of normal.

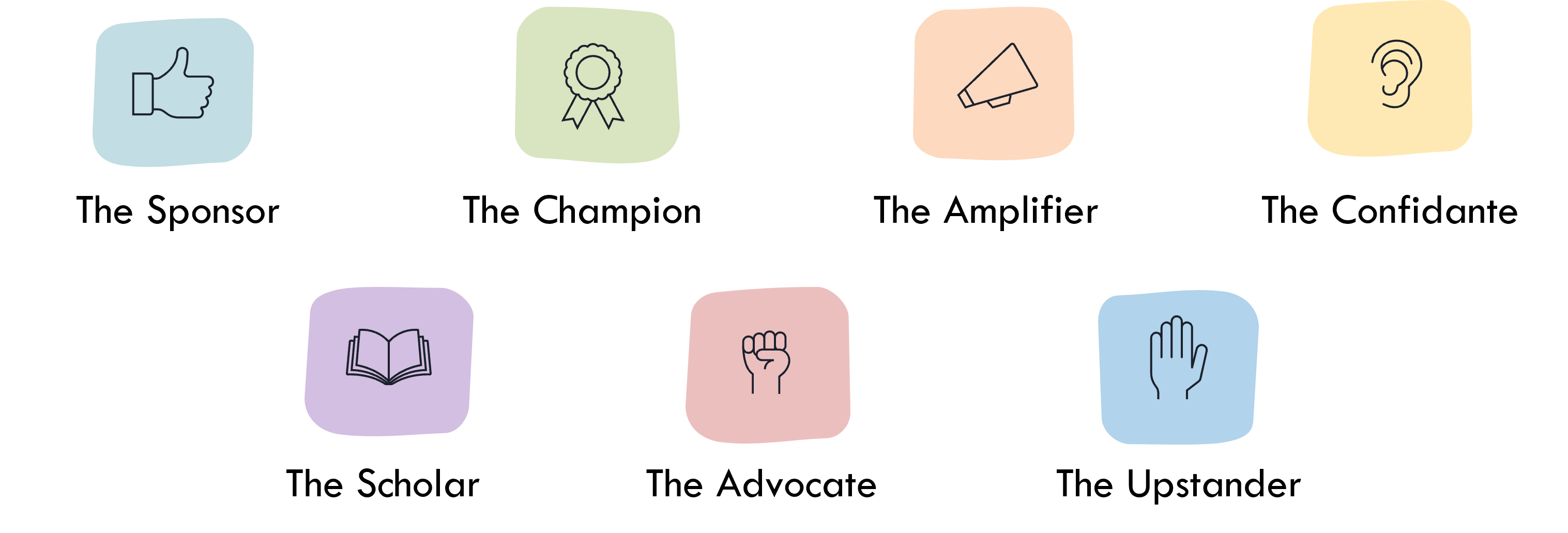

But Phil’s approach is to point directly to what acts of allyship can be. They introduced me to Karen Catlin’s ally archetypes, seven action-sets for allying with others in the workplace:

This simple, symbolic framing helps us think about what kinds of action an ally can take to change workplace culture for greater inclusion.

The sponsor endorses those at risk of being overlooked.

The champion recognises people for their expertise.

The amplifier ensures all voices are heard.

The advocate helps create opportunities for others.

The scholar learns about the experiences and challenges of others.

The confidant hears and affirms the experiences of others.

The upstander intervenes when witnessing wrong being done.

What might this look like for you? Have you had someone advocate for you in the workplace? Listen to you? Make opportunities for you? Shared their platform with you? Celebrate your successes? Do you have the power to do this for others?

Because, of course, acts of allyship take resources. They aren’t pulled from the sky, but ways of sharing our privilege (no matter how limited).

What resources?

Phil and I took turns to share our contributions in the rest of the presentation. Phil has direct experience with workplace community organising, as well as with acts of everyday allyship, and has shared many direct, practical strategies in their post here.

My contribution was more conceptual, locating third space workers’ psychological resources as potential allies. Simplistic though it is, I find the Venn diagram depiction of the third space helpful:

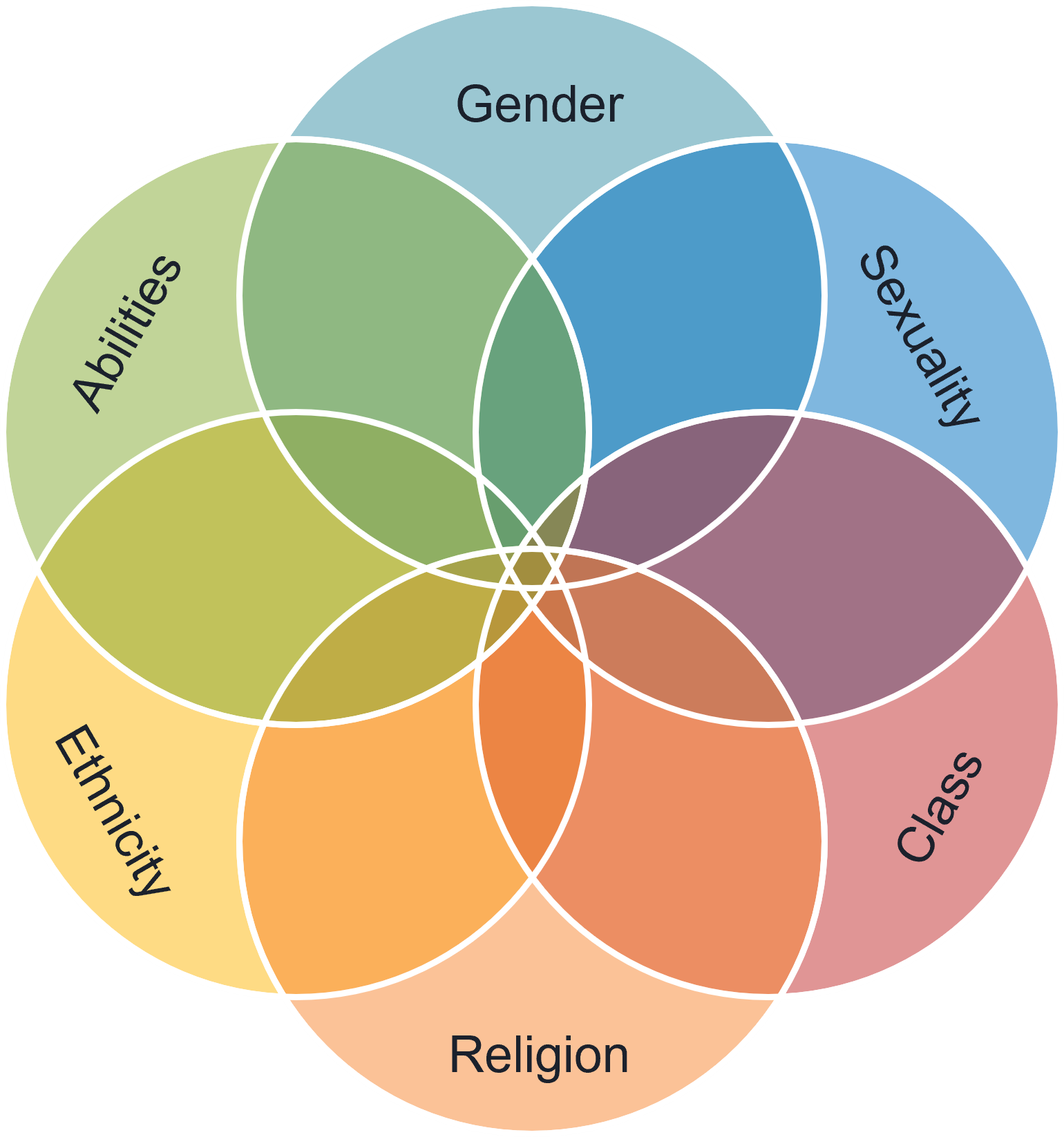

It provides a foothold towards the overlapping matrix of intersectionality (there is no official model, as it’s not possible to capture all the possible dimensions of identity in a diagram like this):

The point is not that only special people have these dimensions, but that everyone does. For some of us, the dimensions of our identities are in harmony—especially if they are largely congruent with aspects of privilege, like whiteness and heterosexuality. For others, the overlaps create sharp disjunctures and clashes—if your ethnic group doesn’t accept your sexuality, say, or your working class culture is at odds with your disabilities.

And when you exist in the university, with its binaries of academic—professional, lecturer—student, the presence of overlaps can force us to choose between fight or flight.

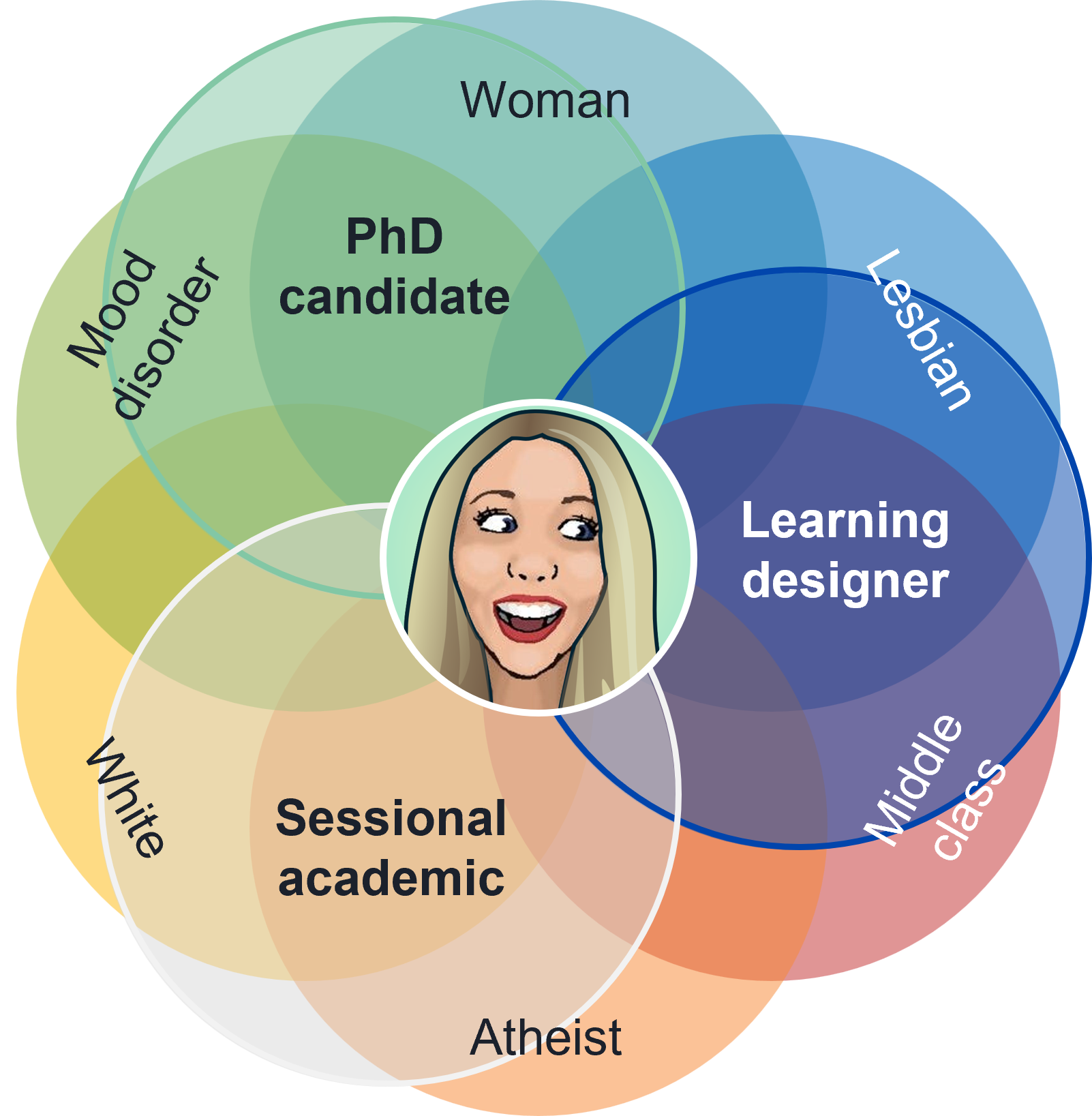

Me: a case study

I’m a lot of privileged things. A lot. I’m white, able-bodied, educated, with financial means and professional status in my field. But even I still struggle with some clashing overlaps between my identities in the university.

Being a PhD student (a humbling role that requires me to act as an intellectual novice) clashes with my years of experience as a learning design specialist who has led teams and projects across institutions. Being a teacher, ironically, also challenges my positioning as a designer, as many of the front-loading principles held dear by design managers are antithetical to the emergent work of teaching. I sometimes feel as though I need to switch off particular parts of myself in order to navigate things without extreme dissonance. Other times I stubbornly declare all my selves at once, but just cause confusion and selective hearing from the people around me.

But what I also have are access and empathy. I have tickets to each arena. I don’t just know what it is to be a student, I feel it. I feel teaching. I feel design. I feel research. And I speak those languages.

This, I think, is exactly what makes an ally. Allyship isn’t about being the same as the person you support; it’s about recognising that you share some things and differ in many others, and so you have opportunities to support them in ways they cannot.

For example, I’m not a “real” academic with a permanent position and a research workload. But people with those things have more resources to advocate for me. I’m queer, but I’m cisgender (I identify as the gender I was born to) so I have a greater degree of safety to advocate for other queer people whose gender identities are more marginalised in society.

(By advocate, of course, I don’t just mean “speak for”—I mean all the allyship behaviours: helping amplify voices, increasing recognition, making an effort to understand more deeply, simply being there and listening.)

So allyship isn’t just about the strong helping the weak.

It’s about recognising that every single one of us needs support sometimes, and every single one of us has support to give.

How do you ally?

For practical allyship strategies, you can learn more from Philip Abramson. As I mentioned, their Substack post below offers direct, meaningful tips for everday and organised allyship work in the academy.

But they’re also an important, authentic voice to follow for values and action on inclusion, accessibility, neurodiversity, mental health awareness and gender diversity in education.

If these are important to you too, follow Phil on LinkedIn—you won’t regret it.

Leave a comment