A recap (or perhaps a wishful revision) of the presentation I gave at the Third Space Symposium, Melbourne 2024

A few days ago I presented a hand-wavey, conceptual, vibey talk at the Third Space Symposium 20241, an event for staff working in the awkward intersections between academic and professional in higher education. The presentation was wibbly wobbly and probably quite bizarre for attendees of a professional conference.

So what was I on about?

The idea of the “third space” in higher education was popularised by Celia Whitchurch, who proposed it as a metaphor for locating the cross-boundary work done by staff who are involved in teaching and learning, but are not lecturers; staff who facilitate research, but are not researchers; staff who manage and coordinate, but are not administrators. This imaginary space is unrecognised by universities, who use a tidy little professional/academic binary to contract their staff.

The thing though?

It’s not a space.

It’s nowhere.

You don’t go to a third space to do your work. You go to an academic space or a professional space, and you try to fit. But you’re always a few toes out of line. You’re not home. You do what you can, and then you move into the other space, and it’s the same. You’re needed, but maybe you’re not quite recognised. You’re still not home.

I wanted to use 15 minutes of the symposium to reflect on that metaphor of “space”. I used the concept of social topologies to suggest a few ways of conceptualising this social construct of work-as-space. These are each potential ways of reimagining the space we currently picture as made up of distances, regions and boundaries.

In brief:

when we think of social space as networked, instead of distance and borders separating us, we’re concerned with who we are connected to and who are aren’t

when we think of social space as fluid, we think of shifting relationships, of borders melting and moving, of every part of the space being moved by every other

when we think of fire space, we think of dynamics that can change instantly, without seeming to move at all.

These are metaphors. Of course. They’re useful insofar as they help us think about social dynamics as a “where”. One of the most obvious examples of networked space is the organisational chart, which maps out where everyone sits in a company, indicating the power structures, the connections between teams, the dotted lines that tell you someone serves two masters.

But this is exactly the kind of model that creates binaries and discomfort for those whose work doesn’t fit in (or under) a box. Networked space with its nodes and links is too tidy, too theoretically comfortable, to really describe the shiftingness of the atmosphere we’re trying to describe.

So might fluid or fire help us think in more dynamic ways?

Here’s my crack at fluid, exploring the properties of continuous motion:

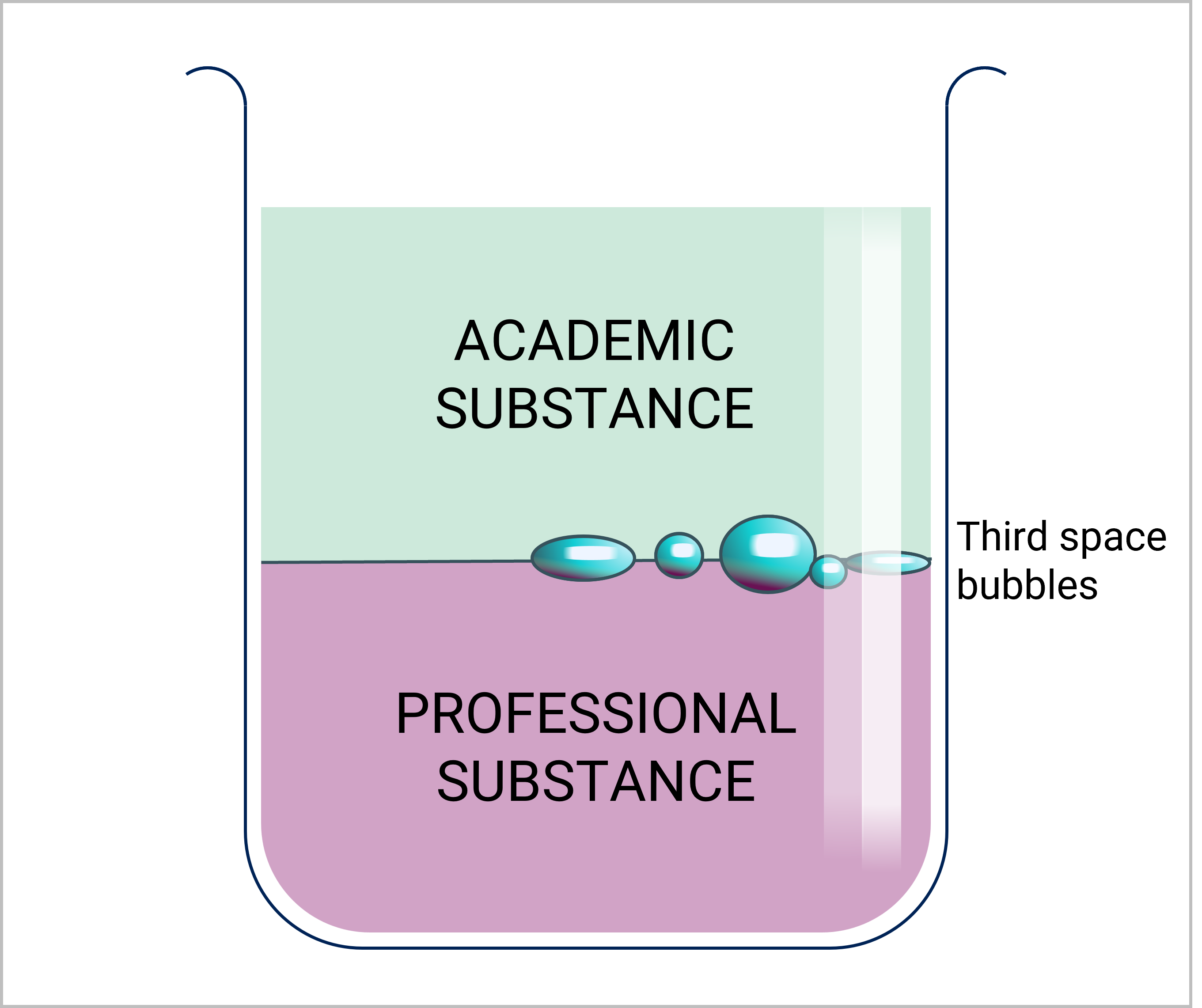

In the beaker, I imagined academic and professional spaces as something like oil and water: theoretically incompatible, but when they are thrown together, capsules of fluid are formed that might be substantively one, yet enveloped in the other and floating between the two, eventually—inevitably—to be subsumed by the element that dominates.

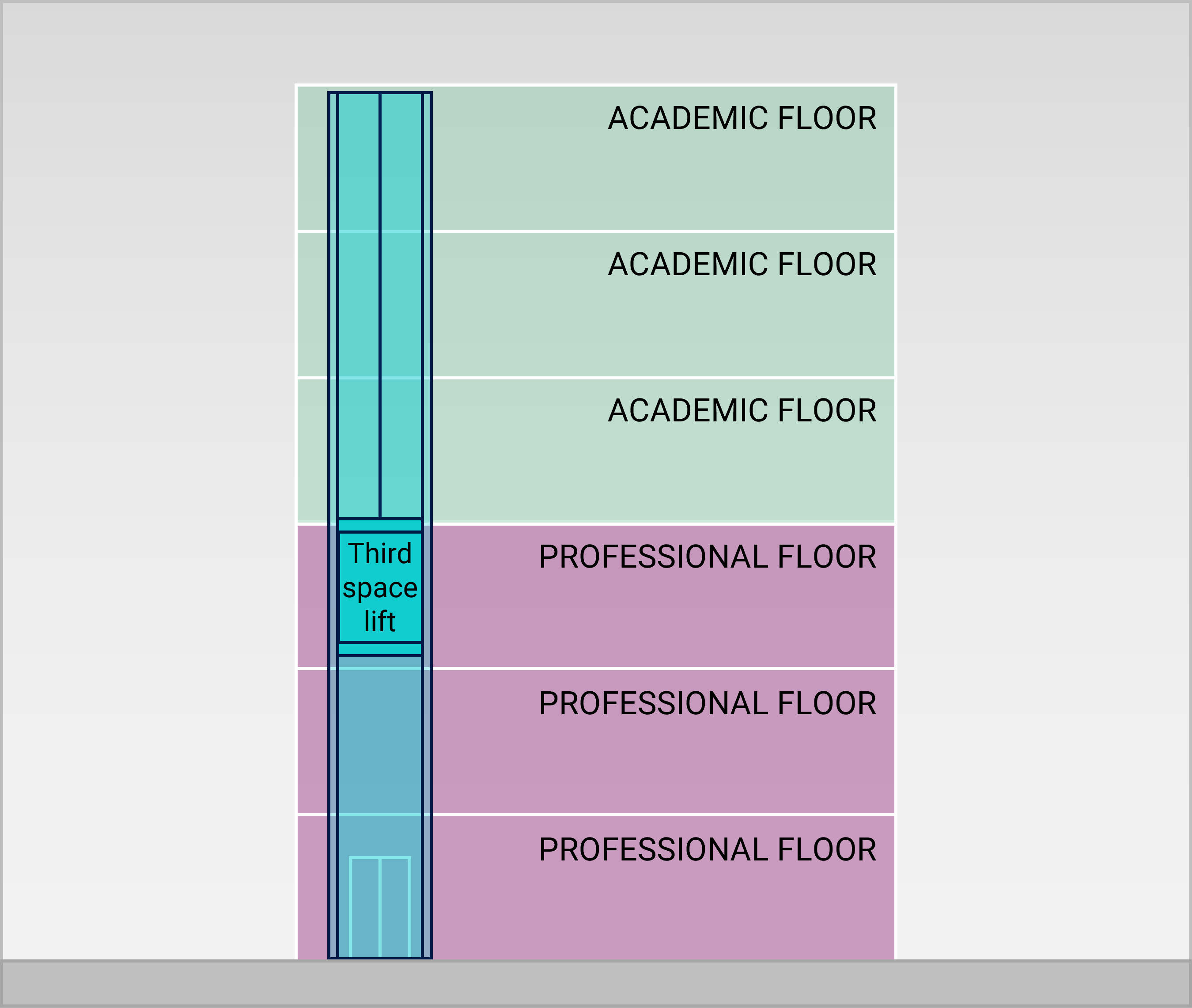

In the building, I pictured the third space as the shaft of a lift that moves between allocated floors. It’s not a habitable environment—rather, it’s a utility space, a transport zone, designed specifically for people that need to be somewhere else.

Fire, though, I struggled with.

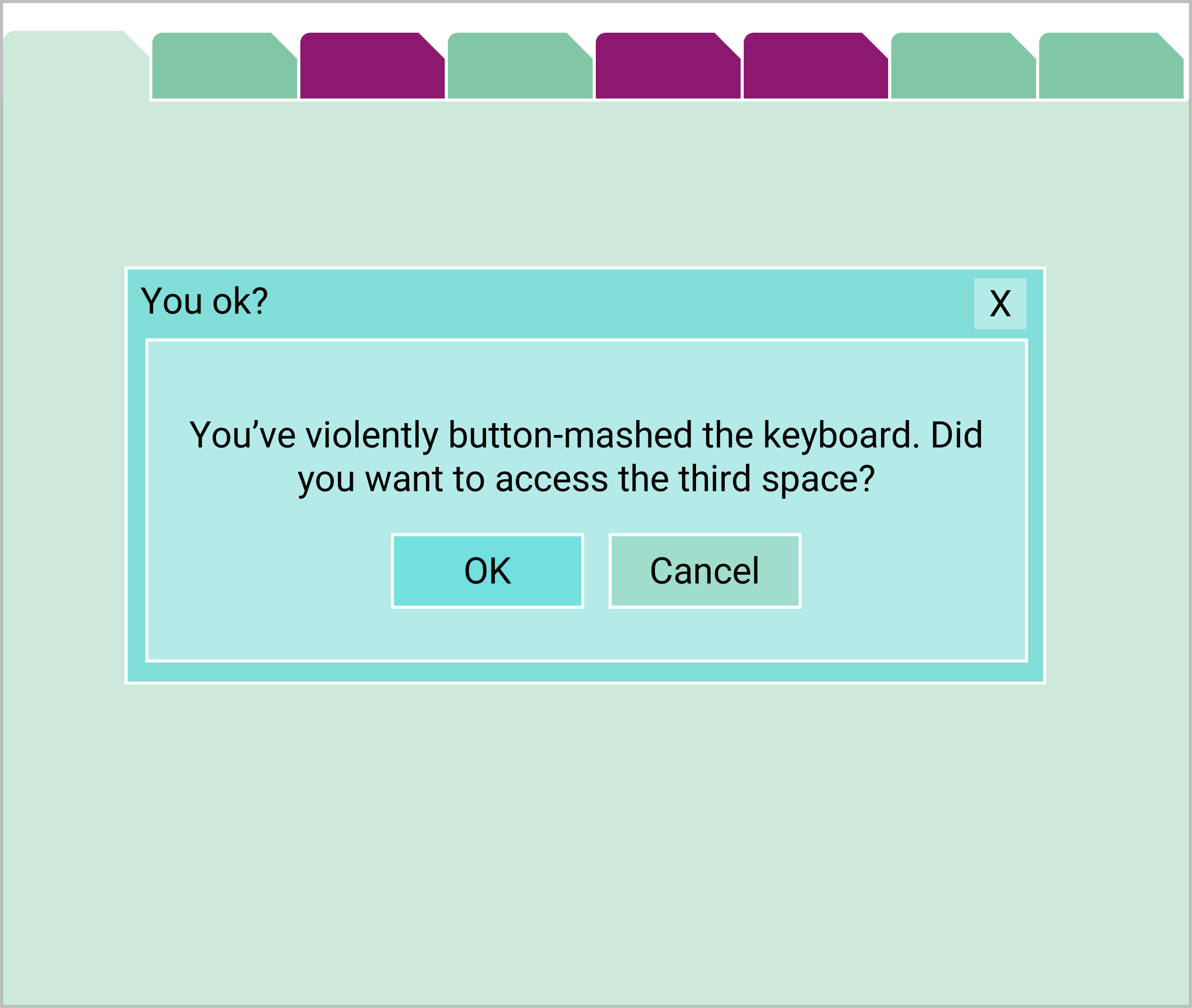

When I think of fire space, the only thing that comes to mind is the computer screen. I think of tabs, dialog boxes: things that jump into existence on our monitors, and just as instantly disappear as we choose “ok” or “cancel”. I think of the kind of code switching work that people must do invisibly when navigating multiple cultures, constantly watching for cues that tell them which version of themselves to be today.

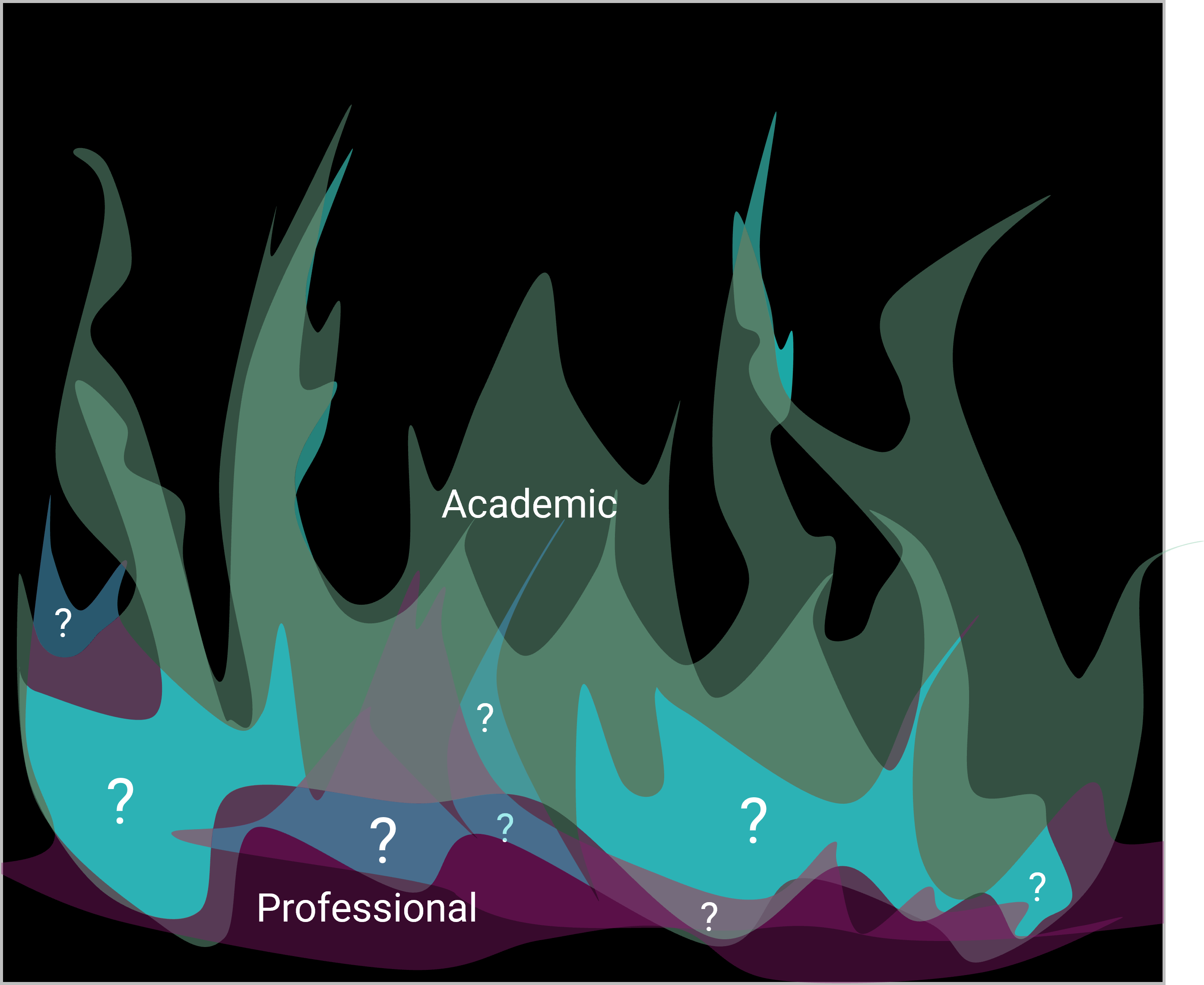

I also just wanted to try drawing fire. I didn’t expect good results, but sometimes art’s power comes from slapping paint on the canvas and just listening to the feedback it gives you. I’m not sure it looks quite like fire, but it did allow me to play with the transparencies and leaping overlays of flame, the way they create ephemeral impressions of shapes and colours that aren’t there, that were never there, that were the result of energy and light and your eyes trying to make sense of the chaos.

What I really wanted to ask was this: what kind of materials are we actually trying to play with when we think about the architecture of third space? Spaces, their materials, their shapes, and their inhabitants, create affective atmospheres which are shared and which affect who and how we are within them. So what imaginary do we share of this concept? Or do we, in fact, not share the same imaginary at all?

How might we shape the third space imaginary in ways that benefit each other?

The third space isn’t a space. It’s not a thing.

That’s the problem.

What thing would we like it to be?

- Massive gratitude to the TELedvisors organising committee, especially Penny Wheeler who introduced me, Colin Simpson who gently challenged me, and Keith Heggart who affirmed my becoming-academic identity. Thank you for making this space for me! ↩︎

Leave a comment