This is a classic Miriam gush-post about the role of money in negotiating value (featuring pirates).

I think about money a lot… but not in the way you think.

One of my special-interest rants is about pirate silver, otherwise known as “pieces of eight”, or formally the Spanish dollar, peso or real.

The coins were literally worth their weight in silver. Peso translates to “weight”; a peso was minted from 25.563 grams of fine silver. The silver from which it was made, and the techniques used in minting, meant that Spanish currency was uniquely reliable as a unit of exchange. Regardless of whose crest was stamped on the face, a piece of eight would be recognised as currency worldwide by the 1500s and traded on the seas.

OK, they weren’t really that big a deal with Golden Age pirates. Pirates spent way more time going after actual usable stuff, like fabrics and sugar and medicine, than they did silver or jewels. Why? It was all about what could be traded fast. A huge physical stack of cash was a fairly huge (and heavy) inconvenience, especially when so much of the money going around was of questionable value.

But Spanish dollars were different. You knew with a piece of eight that the silver purity was good. You could quickly tell when someone had tried shaving a bit of silver off the edge, because the edges were milled (ridged). And you knew the next guy would know it, too.

Bonus tidbits:

Why piece of eight? One “real” was worth eight “reales”.

No change for a dollar? No problem — just clip up the coin into quarters or eighths. The weight and quality of silver was so reliable that a lot of people would accept the clippings, too.

This is the coin upon which all modern dollars were based. It was actually legal tender in the USA until the mid 1850s. “Two-bit scum”? Why, you’re worth nothing but a couple of clips off a real coin, ya rat.

Why do I love this? Basically, I’m fascinated by the way these coins enabled an international agreement about fair exchange of value. It was an agreement so strong that it unified the legal and the lawless across oceans and continents for hundreds of years.

We don’t use money that’s worth its weight in anything any more. All money is “fiat money”, which basically means it’s legally worth what we say it’s worth because we say that’s what it’s worth. The moment somebody says that’s not what it’s worth, its value is in question, and we’re in trouble.

(Technically speaking, that “somebody” has to be a government, because fiat currency is legal tender, but nobody’s arguing that governments aren’t at the mercy of markets.)

We went from commodity money (the coin has intrinsic value as a commodity, e.g., silver) to fiat coins (the coin looks like, but isn’t, a commodity) to fiat banknotes (paper that says what you’re supposed to believe it’s worth) to lines of digital code. The ways in which we trust in our money’s value have evolved profoundly. I won’t try to pull a pun with the term “real”, but you know I could if I wanted.

In any case, the point is that money doesn’t have value; it only stands in for value. Borrowing from Brian Massumi’s definition of money (in Thesis 8), money creates a cycle always pointing to, but never being, value.

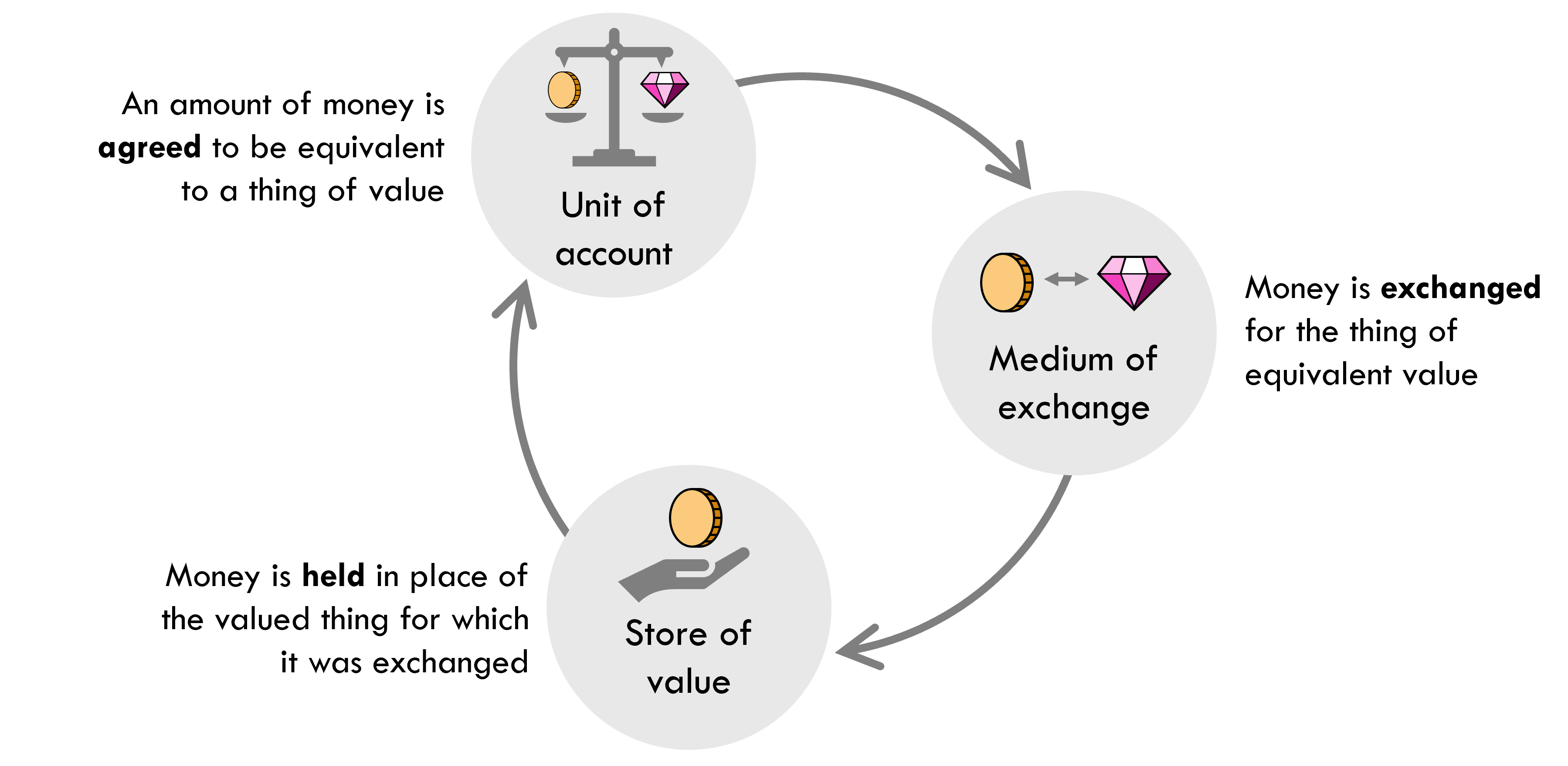

It works as a unit of account, a medium of exchange and a store of value:

You can see why pirates usually went for the sugar.

I’m not an economist. Obviously. But I’m trying to develop an understanding of the relationship between money and value because I think it’s the key to understanding our ideas about value itself.

Commonly, we consider value to be something different, or separate, from values. Value is seen as quantifiable and exchangeable for the right price, while values are qualitative and “priceless”. In essence: anything with value can be measured and traded.

But, of course, there is no longer any weight to measure. In the absence of an intermediary commodity currency, everything is worth what we say it’s worth because we say that’s what it’s worth. The quantification of value is a fiction; all value/s are negotiated qualitatively based on our feelings, mutual beliefs and trust in one another.

I’ve plenty more to say about pirates and their relationship with value/s… but that’s for another day. The real star here is the Spanish dollar and the diminishing echo of its legacy.

Leave a comment