So many governments, institutions and innovation gurus are calling to pare education “back to basics” — but what are the basic provisions of education?

A few weeks ago, I told someone I didn’t think education was only about learning. Here’s what I said (edited slightly for focus):

… education (as a system, as an institution, as a part of society) is not just about learning. And it shouldn’t be, either. When we try to reduce education down to teaching-and-learning, we always end up thinking what we have is a terribly inefficient mess that doesn’t do its job very well at all. Which, if we compare the life outcomes of kids who accessed 12-13 years of school and kids who didn’t, we can see is patently not the case. […]

10 years as a learning designer, learning is my focus but I’m currently taking some time to zoom out and look at where that learning sits and why. (because if you think about it, going to school is really the most complicated and inefficient way you could think of to learn something…)

After this, I felt an obligation to articulate my thinking a little more. I spent some time reflecting on what education actually provides to students.

Biesta’s three purposes of education (qualification, socialisation, subjectification) were present, but they were not primary. Why? Because although they are purposes of education, they are not exclusive to education. One can become qualified in other ways; one can become socialised in other ways, and so on. But what collection of things does a formal education provide that can’t be obtained any other way?

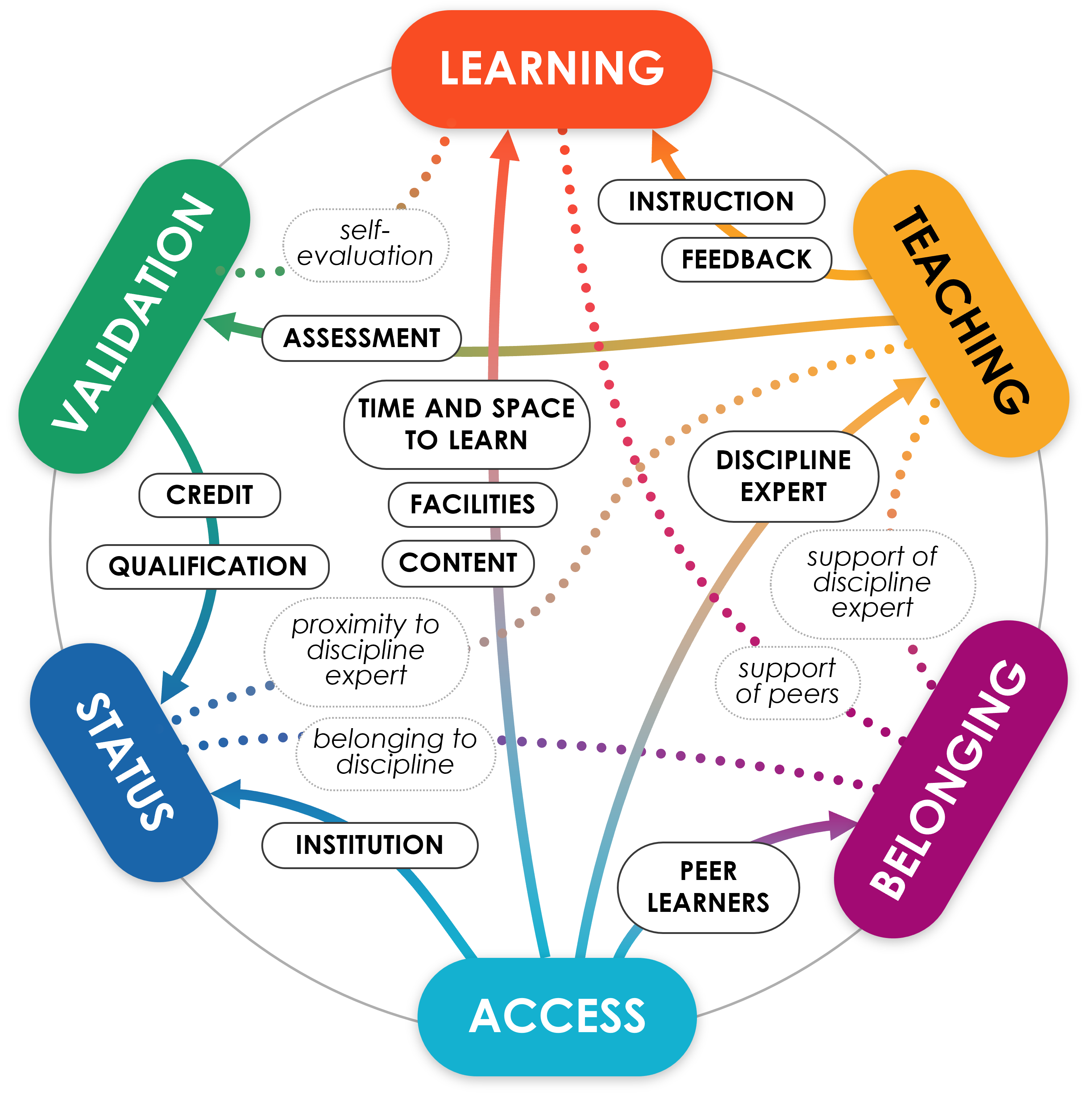

Here’s what I came up with.

Six provisions of education

Access. Access to content, facilities, time, experts and the support of peers.

Teaching. Instruction and feedback from a discipline expert.

Validation. Assessment, credit and qualification from a recognised institution.

Learning. Gaining skills, knowledge, self and social awareness.

Status. Association with the institution, the discipline, and the qualification.

Belonging. Acceptance and inclusion in a peer group, institution and discipline.

The point is not that each individual provision can only be gained through education, but that the combination of six is unique to education provision.

The first three — access, teaching and validation — are tangible provisions, while the latter three — learning, status and belonging — are intangible, fuzzy, abstract. We can provide access to spaces, facilities, teaching staff, content, assessments, certificates. But support, self-awareness, inclusion are felt things, things which emerge from the educational assemblage.

So in my sketch, I’ve tried to show those tangible things with thick, unbroken lines, while the intangible relationships and outcomes are dotted, faint, tacit.

What’s missing from this picture?

I’ve deliberately left off the “how” for now — so there’s no mention of pedagogy, modes of access, quality of content, learning experience, or types of assessment — because I think we are so caught up in questions of how that we are at risk of not noticing when parts of the “what” are taken away from us.

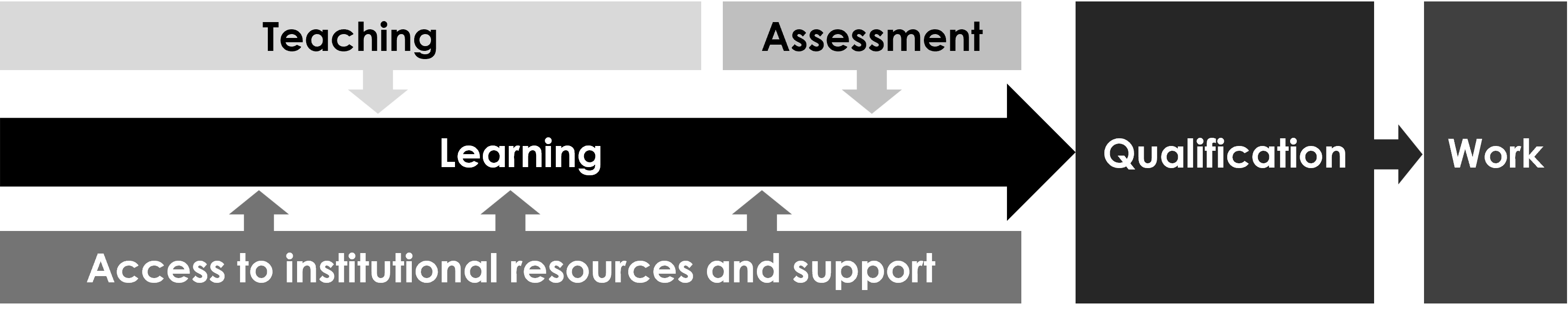

For instance, what’s missing here?

This is a fairly standard sketch of the way we tend to imagine education being provided to a student. The whole educational project is propelled forward by learning, supported by teaching, assessment and administrative support, leading to qualification and (almost invariably) to paid work. But how could we incorporate status or belonging into such a diagram? What would these elements do to the pleasing forward flow of this chart?

Over the past two decades or so, various “innovations” have sought to unbundle these provisions in tertiary education. Some micro-credentials are offered as “assessment only”, so that learners get only validation and status. Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) in VET achieves about the same — students’ prior results are validated towards award of a qualification, and that’s that. Many MOOCs are focused entirely on providing self-paced learning content with non-valid quiz assessments at most, omitting validation and belonging (though arguably still retaining status when the course is offered by a recognised institution). The same critiques as ever are leveled at online education, suggesting the online mode fails to provide equal access or belonging.

How well would this analysis apply to compulsory schooling? If you were to map this onto a non-school learning context, would it still fit? Are there contexts you’d call “education” that don’t look like this?

I’d love your thoughts.

Leave a comment