A response to Biesta’s social imaginary of teacher as “pointer”

I attended a presentation by Gert Biesta as part of the European Conference on Educational Research series on social imaginaries. As always, he spoke slowly and lyrically in his curling Dutch accent, and I felt almost like I was receiving a massage as I listened. I love hearing Biesta speak. But I’m starting to realise I don’t agree with all he says.

The presentation was largely focused on how teachers might be positioned within the “education of the future”. A number of Biesta’s signature theses were outlined, including the plague of “learnification” language; the value of schooling as a “free” time (that is, free from the expectation to be productive, rather than free to do anything at all one desires); and the role of the teacher as “pointer” when one asks, “what is the point of education?”

I have already written about learnification and its misdirected critique of “learning” language as a key driver of the devaluation of teaching and the consumerism of education. While language unquestionably shapes thought and practice, in this regard I don’t think the word “learning” is the one we should be attacking.

The Greek word scholê translates to “leisure” and implies that pupils engaging with their education should be unburdened by external demands of work and society. The notion of scholê as “free time” is not an unattractive dream, but in my view it is not a meaningful one, either. For adults living in organised society, it is patently impossible to claim such “free time”. Economic and social and familial life cannot be paused to make room for education. For children, though it’s tempting to claim scholê as an ideal, life has still already started. Balance is vital, of course. Some children face far too much hardship far too early, while others are excessively shielded, and both extremes lead to struggles of various kinds. Because, at bottom (and Biesta knows this), learning does not happen outside of the world1.

This leads me to the final point, and the one on which Biesta’s presentation concluded: the role of teachers as pointing the way in education.

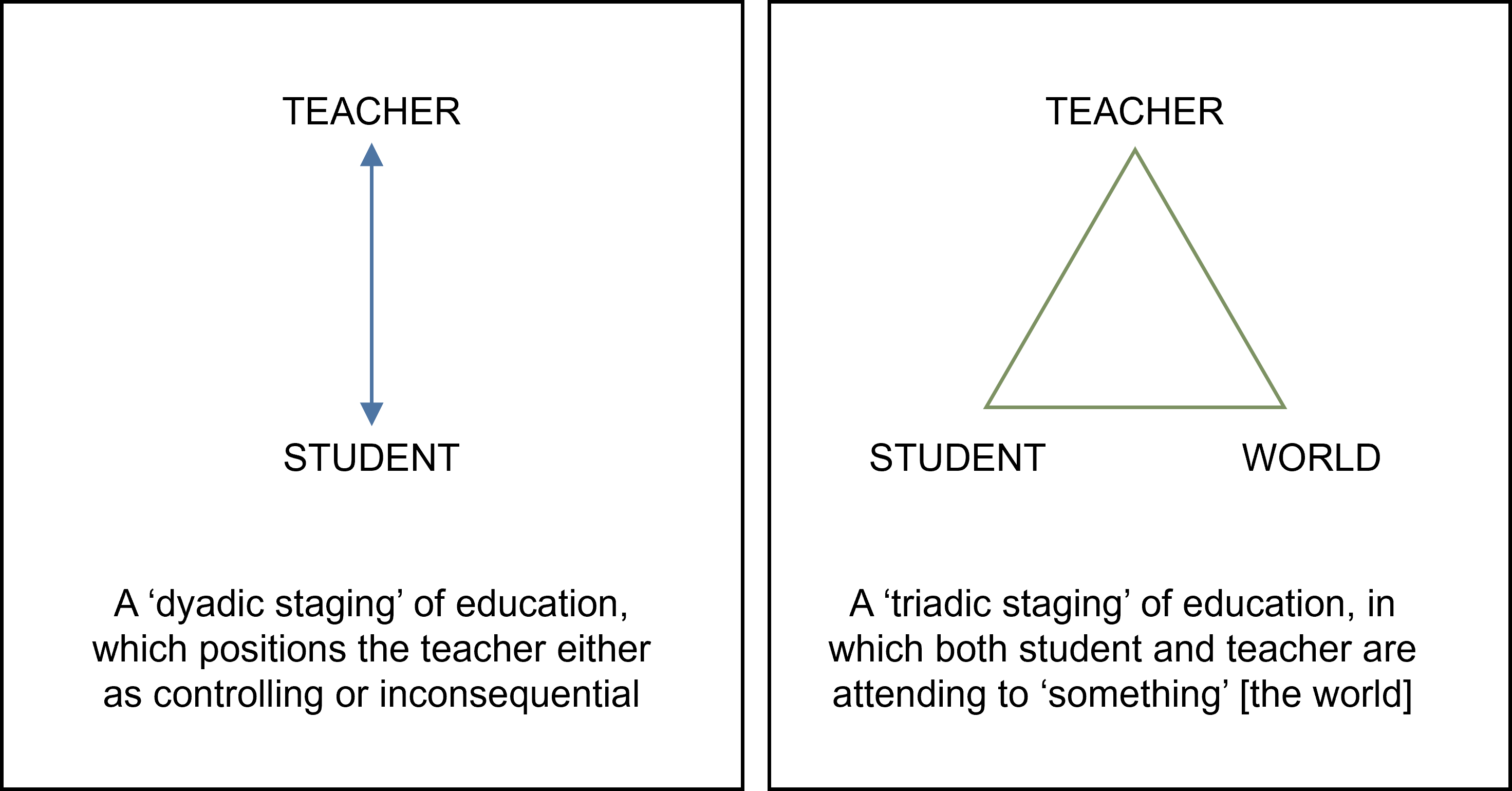

In his presentation, he offered the following diagrams to illustrate:

He acknowledged, as I had mentioned in my own naive musings, the problem of control in the teacher role: where teacher and student are depicted in a two-way relationship, there is necessarily some sense of power relations between them. But in a three-way (triadic) relationship with the world, this tension is released as both student and teacher are attending to the world.

I instinctively didn’t like the triangular diagram, not least because Biesta has placed “teacher” at the top, but also because it offers nothing in the way of illustrating the relationships between the three, and seems to imply the world is an equal party in this dynamic. I understand Biesta’s illustrations aim at simplicity, but in doing so, I feel they block themselves from having any real, meaningful engagement with current or possible future teaching practice.

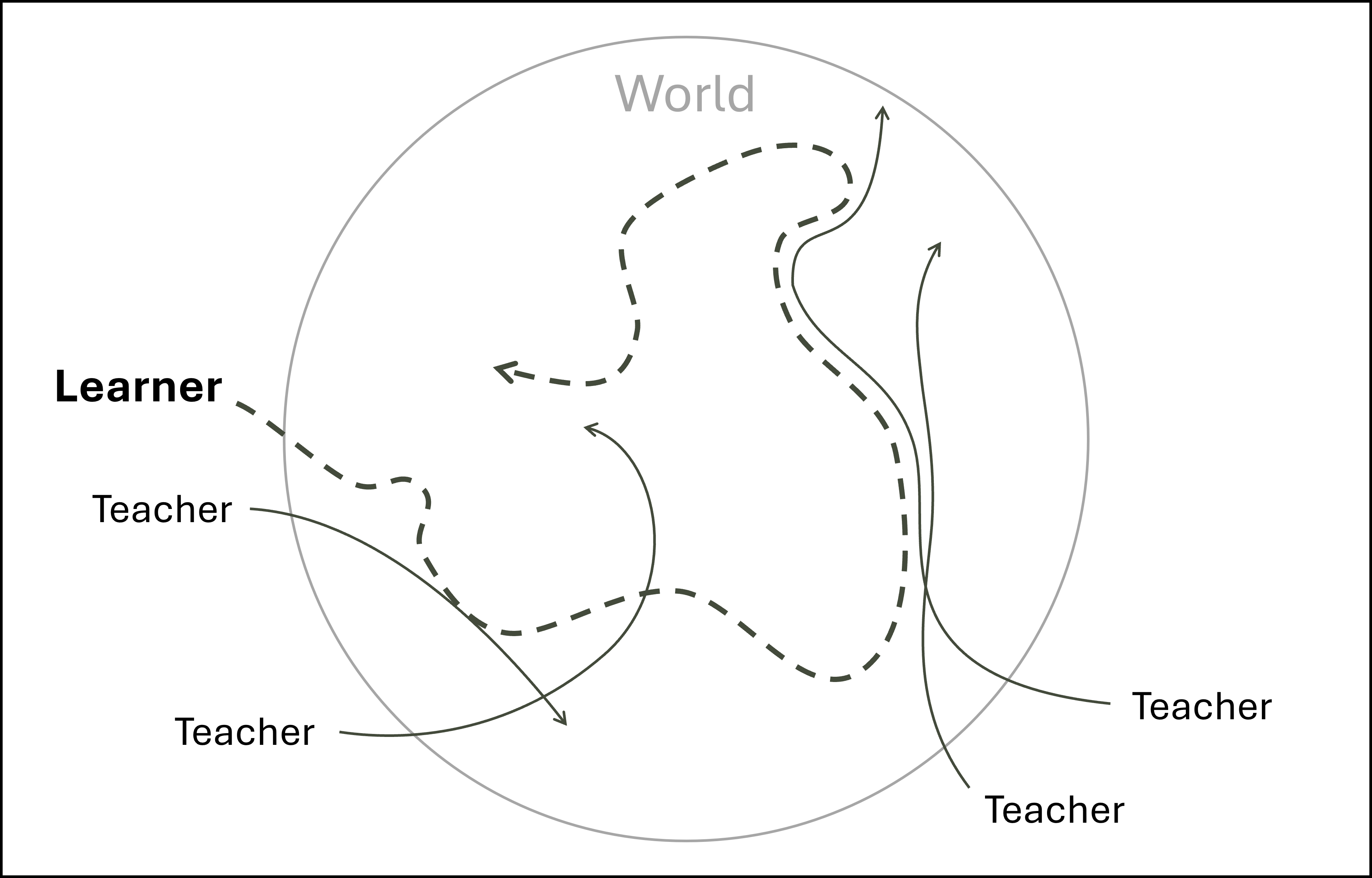

I tried a cartographic2 scribble of my own. It’s not a correction but an attempt to visualise my own sense of the relationships between learner, teacher(s) and world. This has emerged partly from my analogy of learning as a “track” or “path” that a learner explores.

What I’m trying (poorly) to do is show better how teachers walk alongside learners for a time as they navigate their worlds. Every learner encounters many teachers throughout the course of their education. Some teacher relationships are lengthy, some brief; some are epistemologically intimate while others are glancing or loose. I’ve tried to capture some of the ways this might feel. The second teacher, for example, is encountered early on the learner’s path but their trajectories rapidly diverge. Much later in the learner’s journey they find themselves moving towards a worldview closely aligned with that teacher – their paths, or their views, may intersect again.

Yes, I agree with Biesta: teachers point a way forward, which learners may choose to follow, adapt or avoid. Teachers don’t all “point” in the same ways or the same directions. Learners can experience congruity or dissonance between the approaches and directions of the different teachers they encounter. And all of this takes place in the world as the learner sees it (which is why each teacher’s trajectory ends somewhere in the world, and does not exit it or continue indefinitely).

This illustration doesn’t include any acknowledgement of the role of educational systems, which as I’ve previously noted play a vast role in setting the directions in which teachers are allowed to point. It would be interesting to try to chart a concept of “the world” as colonised by “the curriculum” and how teachers’ agency might interact with this powerful gravitational force.

“The world” as Biesta speaks about it is the natural and social environment in which people navigate their lives. He insists that “the world is real and puts limits on what we can do with it”, suggesting a belief in external objective reality. “The world” as I speak about it is, I suspect, ontologically different. While each of our worlds is “real”, we inhabit our own understandings and must negotiate them with others.

Social cartography is an approach I am not particularly familiar with, so I’ve used this term a bit cheekily and with none of the essential engagement with specific texts to inform the mapping. I’ll accept your advice and hopefully your forgiveness!

Leave a comment